Inside the Willson Contreras Trade: Swing Decisions, Pull Air, and the Red Sox’s Long-Term Plan

A deep dive into the Willson Contreras trade to the Red Sox.

The Red Sox and Cardinals linked up for their second trade of the offseason last Sunday night, with the Red Sox acquiring first baseman Willson Contreras and cash for minor league starting pitchers Hunter Dobbins, Yhoiker Fajardo, and Blake Aita. Whispers of Contreras’s willingness to waive his no-trade clause for the right team began circulating in recent weeks, and the Red Sox were one of the teams immediately rumored to be interested.

Here’s what I wrote about Contreras in my offseason preview back in October:

“Of the trade options Willson Contreras is the most appealing, but he has a full no-trade clause that he was unwilling to waive last offseason. It’s still worth calling old friend Chaim Bloom to see if this has changed. St. Louis’s direction was up in the air last year amid the transition in their front office, but with Bloom now fully at the helm, they’re starting to signal that they’re headed for a traditional rebuild. I’m not getting my hopes too high, but there’s at least a chance that changes Contreras’s perception of staying.

Contreras was great defensively in his first season at first base, and there’s still a lot to like with the bat. His walk rate was uncharacteristically low last year but he’s just a year removed from a .380 OBP and performs well in a lot of the offensive metrics the Red Sox value. He has two guaranteed years plus a club option at ~$18 million per season. The money and the leverage the no-trade clause gives him would make his acquisition price pretty low should he choose to waive it and join the Red Sox.”

This is a fantastic move by the Red Sox, addressing both their need for additional thump in the lineup and defensive competency at first base. Contreras has been one of the better right-handed bats in the league for quite some time, but is often overlooked as such because the demands of catching and some tough luck injuries have limited his playing time. He doesn’t appear on many counting stat leaderboards as a result, but his 130 wRC+ ranks 10th among all qualified right-handed hitters in baseball since 2022. He’s just one spot behind Pete Alonso, who posted a 131 wRC+ over the same span, and just 8 points behind 6th-ranked Vladimir Guerrero Jr., who comes in at 138.

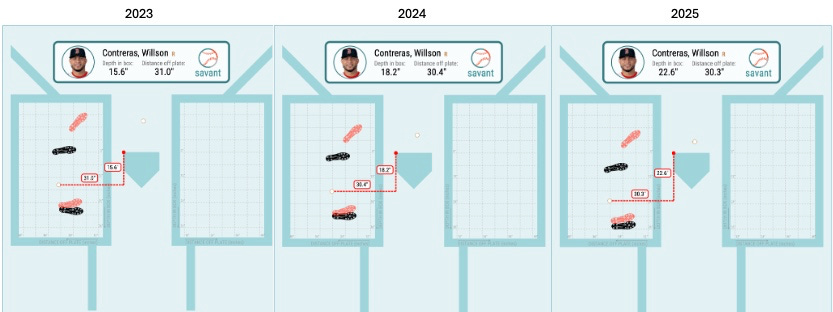

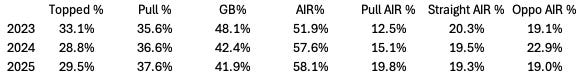

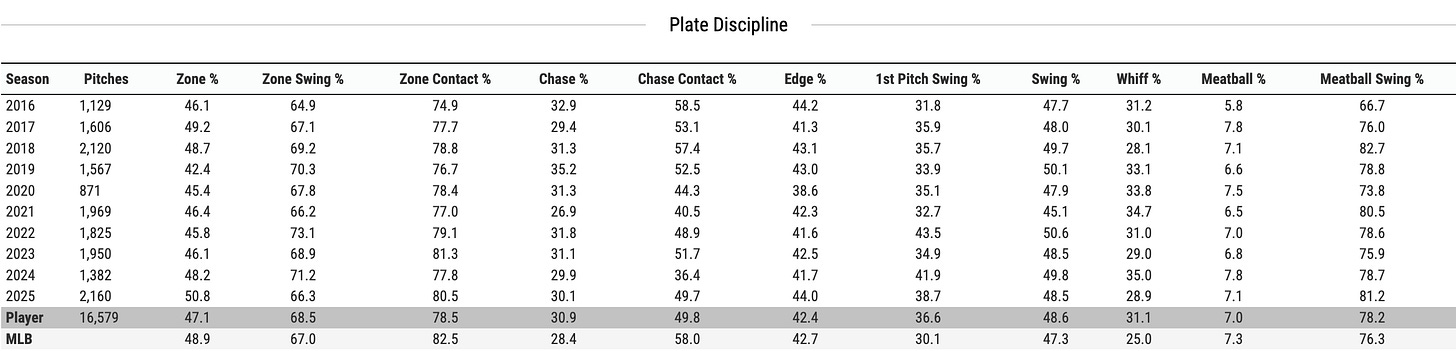

The particulars of the trade have been discussed at length at this point, and two of the most prominently identified trends have been Contreras’s increase in Pull Air % to a career-high 19.8% and decrease in walk rate to a a career-low 7.8% in 2025. My initial instinct was that these two things could be related; that, perhaps, Contreras had moved up in the box, allowing him to catch the ball further in front of the plate, but also forcing him to make swing decisions earlier. If this were the case, then it would be doubtful that he could maintain his Pull Air % while simultaneously improving his walk rate. What I found was that these trends may very well be related, but in almost exactly the opposite way than what I thought. Since 2023, Contreras has actually been steadily moving BACK in the box.

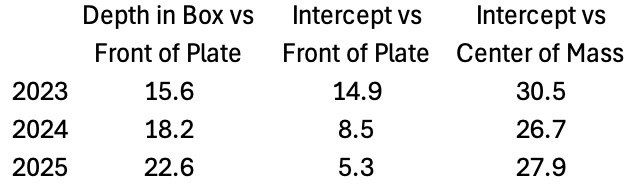

In 2023, Contreras’s average depth in the box was 15.6 inches, as measured from the front of the plate to the center of his body. This placed him among the top 10 closest standing hitters to the pitcher (min 100 swings) of that year. In 2024, his average depth increased to 18.2 inches, placing him just inside the top 20, and in 2025, it increased to 22.6 inches, tying him for 56th. He subsequently went from hitting 46.1% of his balls on the ground in 2023 to 41.5% in 2024 and 41.8% in 2025. Swinging at pitch types designed for weak contact further out in front of the plate often allows them to dip just barely under the barrel of the bat, forcing contact with the top of the ball. Contreras’s Topped % indeed decreased with the change, going from 33.1% to just below 30% in 2024 and 2025.

So the primary mechanism at play here wasn’t Contreras moving forward to pull the ball more, but rather, moving backward to hit more balls in the air. A few more of those balls happened to be pulled in 2025, though, so something else had to be at play here. That’s when I realized that what’s important if a hitter is trying to pull the ball isn’t necessarily where he contacts the ball relative to the plate, but where he contacts the ball relative to his body. Isaac Paredes, one of the game’s most prominent pull artists, stands as far back in the box as anyone in baseball, for example, but still manages the league’s highest Pull Air % by hitting the ball 37 inches in front of his center of mass.

Sure enough, Contreras did contact the ball further in front of his body on average this season, making his contact 27.9 inches from his center of mass in 2025 vs 26.7 inches in 2024. This could be related to one of two things: his timing or a change in his average swing path, which we’ll get to later. You can also see here that his intercept vs his center of mass was the highest of any of these years in 2023, demonstrating just how far in front he was getting to induce all those ground balls. His intercept vs the front of the plate ranked 6th closest to the pitcher in that season. It was quite extreme.

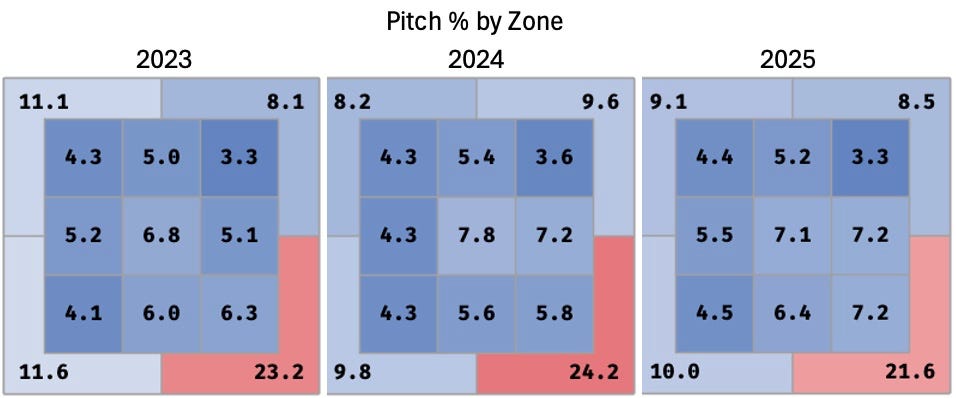

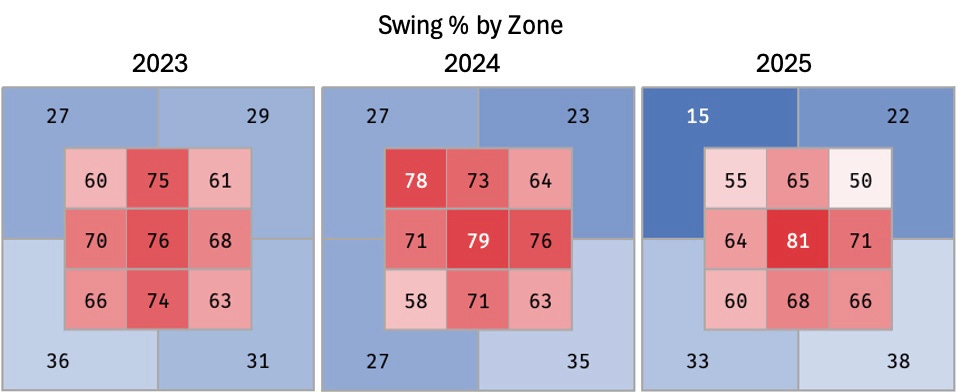

Now back to the walks. One might intuitively expect that a move backward in the box would lead to a higher walk rate — since that would allow more time for swing decisions — but that’s not what happened for Contreras. On the contrary, Contreras’s walk rate plummeted to 7.8%, a level that’s totally uncharacteristic for him since his previous career low was 8.9% in the shortened 2020 season. The reason for this wasn’t immediately clear. He didn’t swing more aggressively on the whole than he did in 2024, when he ran a career-high 12.6% walk rate. In fact, the opposite was actually true, as Contreras swung less overall in 2025. It’s not as if he was pitched significantly differently either. It was still mostly down and away, same as it was in 2024, and only slightly more concentrated in the zone.

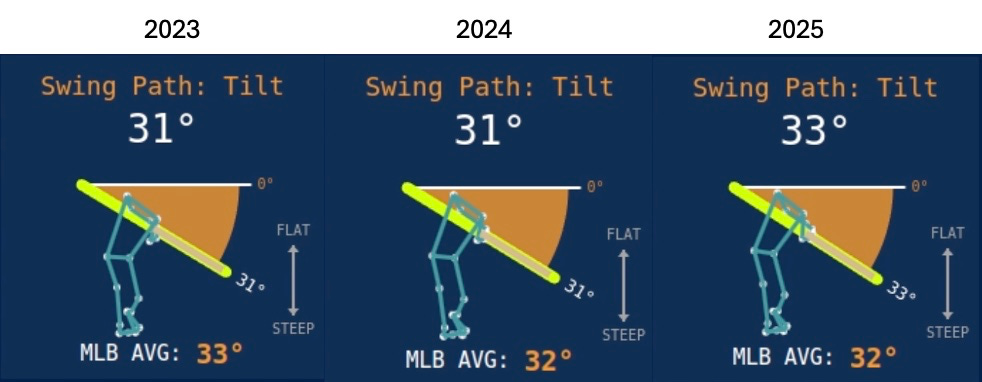

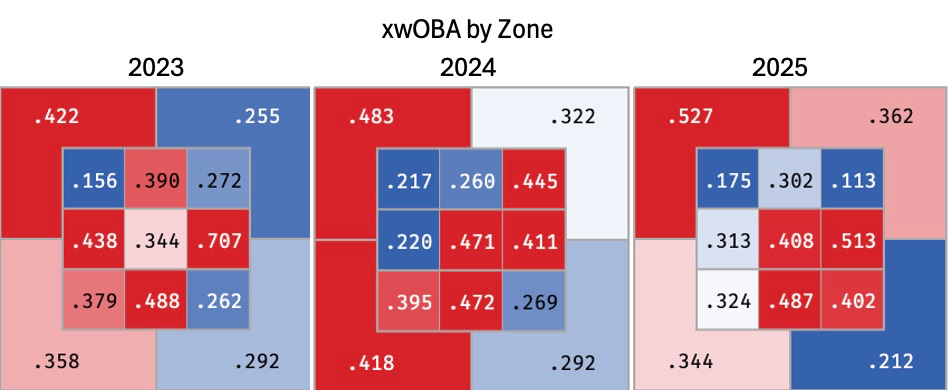

So what gives? The answer seems to lie both in what he was swinging at and how he was swinging at it. First, we’ll tackle the change in how he was swinging. In 2023 and 2024, Contreras swung the bat at a 31-degree angle, or “tilt”, on average. In 2025, that angle got steeper, landing at 33 degrees on average. That might not seem like much of a change, but a move from 32 to 34 degrees was one of the key components to Pete Alonso’s resurgence this year, so it makes a difference. If Contreras knows he’s going to be pitched low and outside, it makes sense that he would adjust his swing to better reach that area. It shows in his whiff rate on those pitches, as he whiffed 64% of the time on low outside pitches in both 2023 and 2024, but just 59% of the time in 2025. Alonso showed similar improvement to his whiffs in that zone after making his adjustment.

It doesn’t seem like this change was worth it for Contreras like it was for Alonso, though, and this is where the swing decisions come into play. He swung at pitches low and outside the zone more often (from 31% in 2023, to 35% in 2024, to 38% in 2025) and didn’t do an overwhelming amount of damage when he did. It also made it more difficult for him to cover the high-outside corner, where he did a ton of his damage in 2024. He was both more passive in that area and did significantly less damage on contact, as flatter swings perform better at the top of the zone. Though he did see improvement in his performance against breaking and offspeed pitches, the ones most likely to be thrown low and away, his performance against fastballs dipped.

That was a lot of information, so let’s regroup. We’ve identified four levers at play here:

Depth in Box

Intercept from Center of Mass

Swing Tilt

Swing Decisions

The adjustments in Contreras’s swing tilt and swing decisions certainly appear to be related. Whether they were made intentionally or were the result of eroding plate discipline is anyone’s guess. Maybe I’m just being optimistic, but I lean toward them being intentional yet misguided responses to a career-high whiff rate in 2024, since other measures of Contreras’s plate discipline came in right around his career norms. He wasn’t any more free-swinging than normal; he just attacked a different subset of pitches.

What we don’t know is whether the shift in Contreras’s intercept from his center of mass, the mechanism that allowed him to pull the ball more in 2025, was a function of his adjusted swing path or a function of him moving back in the box but timing his swing earlier. To definitively answer the question of whether he can improve his walk rate while maintaining his career-best Pull Air, this is the information we would need.

If indeed the swing tilt adjustment was the primary mechanism for Contreras’s improvement in Pull Air, I’m skeptical that he’ll be able to increase both that and his walk rate simultaneously. That doesn’t mean there’s no room for additional production with this approach, however. What I’d recommend Contreras do if he wants to continue on this path of attacking low and outside is move back up in the box to where he stood in 2024. By doing this, Contreras would be able to catch those pitches sooner in their path toward the plate. That, coupled with the additional tilt in his swing, should help his performance on those pitches, since they’re going to be breaking balls more often than not, and they’ll have less time to break away from his barrel as a result of him standing closer. It’s not too difficult to imagine this helping him set a new career high in Pull Air, but we’ll probably see him walk at close to the same rate if he continues to emphasize making contact low and outside.

Conversely, if he abandons his new approach, deemphasizing those low outside pitches and returning to his flatter swing path, his walk rate should rebound. Standing back further in the box could even help in this area, since, if conventional wisdom applies, the extra split second of reaction time should help him with pitch recognition. We’d be likely to see that Pull Air go away, though, since we’re expecting his Intercept from Center of Mass to revert along with the swing tilt in this scenario.

These two scenarios each assume that Contreras’s steeper swing is the reason his contact point was further in front of his body on average this season, but what if that wasn’t the case? What if it really was just a difference in timing? This is the scenario where he could improve both his Pull Air % and his walk rate simultaneously: by abandoning the low outside approach, but still hitting the ball further out in front of his body. I suspect that this is the least likely scenario based on everything I’ve outlined above, as it would track to me that a change in his swing path would have an impact on his contact point as well, but if it is possible to improve in both metrics, this would be the path, and these are the components to keep an eye on.

It might not be such a bad thing, though, if he isn’t able to maintain or improve on his Pull Air % this season. His fit at Fenway — as often is the case with right-handed hitters — is overstated. Take this passage from a recent Fangraphs article by Ben Clemens covering the trade:

“If there’s one concern about Contreras’ offensive fit in Boston, it’s how many line drives he hits. His hardest contact clusters in the line drive/low fly ball area, optimized for distance, whereas Fenway rewards loft, particularly for right-handed hitters. Baseball Savant calculates expected home runs by park, transforming initial batted ball trajectories to each park’s particular conditions and dimensions to approximate what a hitter’s production might look like if he played 100% of his games there. For his career, Contreras’ batted ball mix would produce very few home runs in Fenway, as it turns out, with the Monster turning many into smashed singles or doubles. In fact, only cavernous Kauffman Stadium would be a tougher home run park for him, per this calculation.”

In this way, a reversion to a more oppo-oriented approach might be beneficial. It’s easy to picture Contreras making his money lining doubles into Fenway’s spacious right-center field gap as others like Xander Bogaerts and JD Martinez have done before him. The allure of the Green Monster can have a psychological pull on many hitters to take advantage of it, but maybe that’s not the best thing for Contreras’s style of hitter. It might be for the best if Contreras exchanges more of those lost homers for doubles to the bullpens instead of crushed singles off the Monster.

I wish I had a crystal ball to tell you exactly where Contreras is going to go from here, but these are the factors at play. What I can tell you is that Contreras’s bat speed remained in the 95th percentile last season despite his advanced age, so I don’t see a huge regression cliff on the horizon.

The financial piece of this deal shouldn’t be overlooked either. It’s well worth noting that Contreras’s contract (assuming the $20 million option for 2028 is not exercised) comes off the books at the same time as Masataka Yoshida and Trevor Story. That bit of financial flexibility is hugely beneficial to the long-term outlook of the team, as it would give them an opportunity in 2028 to dip under the luxury tax line and reset the dreaded repeater penalties that have coaxed John Henry into drastic negative actions in the past. Or, on the more optimistic side, this could free them up to make a big splash right as Roman Anthony is starting to approach his prime. Either way, it’s a convenient part of the trade and really great financial management by Craig Breslow.

Overall, I’m very happy with this trade, and always preferred this route to the pursuit of Pete Alonso as a first baseman (if Pete were to DH full-time, I might reconsider). Infield defense was a major priority for me this offseason, but with Trevor Story reportedly sticking at shortstop and Alex Bregman still in limbo, it seemed like the right side was the only place the Red Sox could feasibly expect to improve. For that reason, adding a plus first base defender who can also hit was always the optimal maneuver to me, particularly if it were done by Christmas. I thought that this type of addition would come in the form of Kazuma Okamoto, but this works just as well, with added certainty since Contreras is an established big leaguer and perhaps a shorter term that better fits their financial planning. Now the rest of the infield chips can fall where they may, with plenty of options still on the board and less pressure because you’ve added an all-around contributor at a position of weakness.

We’re still two months away from pitchers and catchers reporting, and much still has to be done to get this team where it needs to go. But this was an important step in the right direction, and at a modest acquisition cost, the Red Sox added one of the best all-around players available this offseason.

Red Sox’ Kristian Campbell wraps up Winter Ball while refining his skill set for 2026

Red Sox’ Kristian Campbell wrapped up winter ball in Puerto Rico as he looks to close the door on the his 2025 rookie campaign and prepare for the 2026 season.